Sound Media: Part I – The present time

Theoretical introduction to sound media

2. The acoustic computer: Nervous experiments with sound media

3. Synthetic music: Digital recording in great detail

4. The mobile public: Journalism for urban navigators

5. Phone radio: Personality journalism in voice alone

6. Loudspeaker living: Pop music is everywhere

2. The acoustic computer – Nervous experiments with sound media

The computer has rich opportunities for experiments in journalism and music, and my history must begin here. It is truly interesting that much of this experimentation takes place among ordinary people, at their home computer. Innovation takes place not just in the celebrated media companies such as the BBC, and not just in the laboratories of global corporations such as Microsoft, IBM or Xerox.

I have selected some of the innovations that have been made in sound media due to the computer, and will analyse them in detail. All the examples were found on the internet, through a process of browsing and searching. There is a vocal outburst from a Tasmanian headphone user on YouTube in 2007, there is a little song from a group called God vs. the Internet, which was issued on the music-publishing site Acidplanet.com in 2005, there is a professional radio reportage from bbc.co.uk in 2004, and finally there is a podcast from the US media site This Week in Tech in 2006. But first I will lay out the technological background in some detail.

The multimedia landscape

Already in the 1970s the computer was so central to Western societies that the notion of the information society had taken hold in public (Briggs and Burke 2002: 260). Alongside the computer the internet emerged as a military communication structure built to withstand a nuclear attack from the Soviet Union, but it was not taken up by the general public in the same way as the PC. The internet was really introduced to the public only in 1993, with the emergence of the world wide web (Gauntlett 2000; Miller and Slater 2000; Herman and Swiss 2000). The combination of the computer and the internet introduced an entirely new communication infrastructure into people’s lives.

The internet is a multimedium. It is a collection of cultural achievements that constantly mix with new interfaces. Among the old media that the internet emulates are letters in the post (email), the typewriter (word processing), newspapers (online newspapers), radio (web radio), television (webTV) and file cabinets, not to speak of all the commercial industries that established a strategic presence on the internet during the 1990s, and thereby created the online bookshop, the online library and so on. This diagnosis is well known, and the process has been described as ‘remediation’ (Bolter and Grusin 1999),’parasitic media’ (Williams [1975] 1990) and ‘rear-view mirrorism’ (McLuhan [1964] 1994). Even now, thirty years after the personal computer was introduced and fifteen years after the world wide web became commonplace, the parasitic development of new media continues.

As I stated above, my analysis relates quite particularly to internet experiments among ordinary people. An example can be the uploading of private photographs to Flickr, where people have found the strangest new ways of organizing and presenting photographs to each other. Indeed, a fair number among the population in Western countries are regularly trying out ways of using computer interfaces and software, at night, after work and during the weekends (Rheingold 2002; Manovich 2001; Turkle 1997). And it is not even necessary to know machine language to do so, because software nowadays always has a user-friendly interface where all functions are explained and can accommodate your preferred combinations. There is a solid dose of entrepreneurship lurking in the domestic sphere, and there is a genuine desire to contribute to the better functionality and more meaningful content on the internet (Delys and Foley 2006; Nyre 2007a). If you are clever you can even invent a new killer application, as American teenagers did with Google and Napster.

Domestic life also has much else to offer in the way of mass media. For relaxation, the average Western household has flat-screen TV, perhaps also a surround-sound system, not to forget the good old stereo set. These media are all immersive; the users lie back in their easy chair and surround themselves with the sounds and images. People also have portable equipment for media consumption, such as the car stereo and radio, and wearable equipment such as the iPod or Walkman. The strange acoustic space of the mobile phone is also relatively new. All these media create what Todd Gitlin calls a ‘torrent of images and sounds that overwhelms our lives’ (Gitlin 2002).

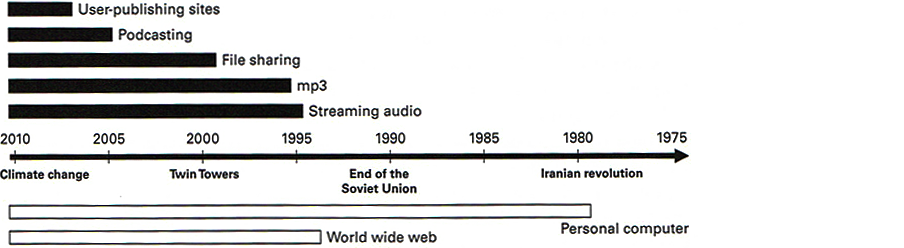

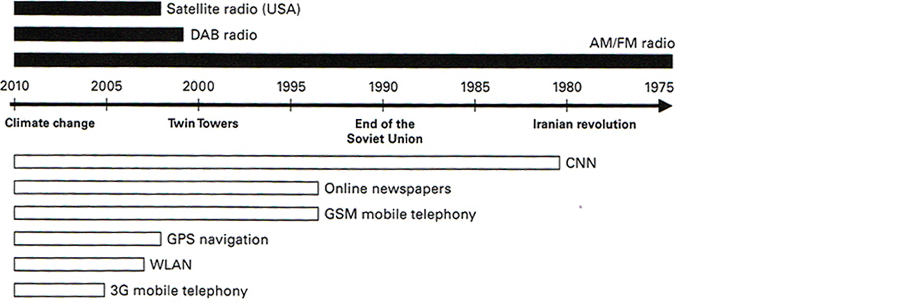

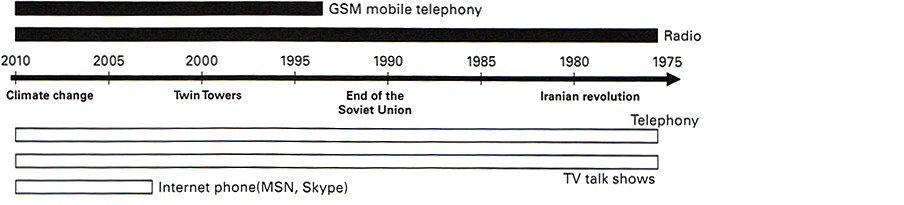

Figure 2.1 shows the audio platforms that I will discuss in this chapter (see also Nyre and Ala-Fossi 2008). Notice that the newest technologies are at the top. Below the line are the two important communication technologies on which the five sound platforms are built – namely the personal computer and the world wide web. It is easy to see that all the developments in question are quite recent, since none of the interfaces for sound on the internet were developed until the early 1990s.

The late arrival of sound on the computer implies that the sound interfaces are anchored in the graphical user interface on the screen and the hand-finger interfaces on keyboards and mice. It is impossible to locate a sound file and play it on the computer without using these basic interfaces. In the future it seems that sound will invariably be embedded in a textual-graphical-visual mix.

User-publishing sites, the newest platform on the list, are a splendid example of the textual-graphical-visual mix. The system is for videos, but it relies strongly on sound communication in the form of music and speech, and also on graphics, flash animations and written text. YouTube had its breakthrough in 2006, just a year after podcasting had been the new and hot platform. In the early 2000s the portable iPod and mp3 player were introduced, and people’s use of computerized sound soared. The mp3 format had been introduced in the 1990s, before file sharing and portable players, and people could start copying their LPs and CD’s to the computer and manage their music collection entirely on this new platform. The first commercially viable platform for sound on the internet was streaming audio, from the early 1990s, and it led traditional FM and AM stations to start streaming their station flow on the web (Simpson 1998).

Making contact with the public

From the 1980s to the late 1990s people in the Western world used modems to connect from their home computers to the internet. After they had turned on the computer, they would painstakingly log on to the internet by calling up the internet service provider (ISP) on a phone number. Now, with broadband connection, the computer is automatically logged onto the internet. But in order to emphasize the live character of the internet, the modem hook-up is a good place to start. The modem hook-up has an acoustics of its own, the strange beeping and whining noises while the modem is trying to synchronize the contact and bring people online. You can hear what it sounds like on track 5.

Track 5: Modern Sounds (0:27).

This is a good example of what I call equipment acoustics. The sound does not have an explicit purpose, but it nevertheless means a lot. It resembles computer game sound, and it also resembles punching the dials of the telephone and waiting for the connection. We can imagine the absolutely live transmission at the speed of light – 300,000 kilometres per second. The modem sounds have a crucial function but no cultural meaning, while techno sounds by artists such as Kraftwerk and Autechre are equally technological on the surface, but have both melody and rhythm, and are rich in cultural meaning.

John Naughton (1999: 16) argues that the wire snaking out of the back of the machine to the modem has changed computing beyond recognition, because it has transformed the computer into a communicating device. The modem makes it possible for the user to hook up with the public in a broad sense. Remembering that the internet consists entirely of modem and broadband connections, it is clear that these connections make the computer into a live medium. At least technically speaking it has the same temporality as radio, television, telephony, and satellite communication, and can contribute to the public sphere in the same way. When the connection is on, we can dispatch messages and read incoming mail, news, etc., but when it is off we have no contact with the wider public, and we must repeat the material we have already stored on our computers.

The fact that the internet is a live medium is an important feature of its public success. The domestic user can monitor public events as they unfold, and the internet also makes it possible for users to cultivate a strictly personal circle of communication, for example on Facebook. The social value of instant connection with others is great, and most people are curious to know what their communication companions have been up to since the last time they were in contact. They can keep track of developments in their field of interest month after month and year after year.

Bolter and Grusin (1999: 197) argue that, although almost everything changes on the internet, one thing remains the same, and that is ‘the promise of immediacy through the flexibility and liveness of the Web’s networked communication’. The stability of live interaction on the internet strengthens it tremendously as a social technology. Online interactive communities can gather from anywhere in the world and engage in what they presume to be a stable collectivity. The benefits of global connection were pointed out by Joseph Licklider et al. in 1968: ‘They will be communities not of common location, but of common interest. In each field, the overall community of interest will be large enough to support a comprehensive system of field-oriented programs and data’ (quoted in Rheingold [1985] 2000: 219-20). For example, the community of music lovers is large enough to support a great range of sub-communities, such as the fan sites for particular artists and sites dedicated to specific musical styles.

Outburst from Blunty3000

On the internet listeners and producers seem to consist of the same kind of people, instead of being neatly differentiated as active producers and passive listeners. If you have something to say in public, whether for personal or political reasons, the internet is at your fingertips. User-publishing sites present the user with more opportunities for expressing themselves in private and in public, and at lower cost of doing so than before. You can, for example, produce a video with software bought at the local computer store, and broadcast yourself on a user-generated website such as YouTube. There is also a general tendency for radio and television stations to capitalize on this engagement through reality TV with interactive websites, and email- and SMS-driven television (Livingstone 1999; Siapera 2004; Hill 2005; Enli 2007).

The first case study in this chapter is a video published on YouTube by a man in Tasmania. This is an example of public expression without editorial screening, something that was almost unheard of thirty years ago. Nobody else can stop you from publishing your stuff, although if it is considered harmful by the providers it will soon be removed from the site. Blunty3000 posted a video commentary on his YouTube area in April 2007. He sits in front of his webcam and argues vehemently that people who wear headphones in public should be left in peace, but all he does for visual effects is wave his arms and hold up a pair of headphones. Therefore the recording is fully comprehensible without the visual feed.

Track 6: YouTube: Blunty3000, 2001 (1:06).

You know, when you see someone looking like this in public, you see a person like me – remarkably like me, more like, maybe look, maybe look exactly like me – and wearing these things on my ears, and I’m in public, and I’m in a store, and I’m looking at a gang cover or something like that, or I’m in a frigging elevator. I mean, that’s the international sign for ‘I’m isolating myself from the rest of the world so I don’t have to talk to you.’ I want myself away, I’m listening to a podcast, or I’m listening to music or I’m listening to the sounds of baby seals being clubbed to death because it makes me giggle! Whatever! I’ve got headphones on, don’t bother me; don’t talk to me. You know I can’t hear you; I’ve got frigging headphones on. These things – if you see a person in the street wearing these things – consider them a cloak of invisibility. Don’t talk to that person, don’t approach that person!

Blunty3000 presents a tirade against people who disturb headphone users. He is loud and rude and sarcastic, and sounds like the internet version of a cowboy, shooting at what he wants to shoot at, and abiding by his own laws. Blunty3000’s behaviour resembles that of a stand-up comedian who plays a carefully rehearsed role, and indeed his exaggerated frustration and shouts suggest that this is a rehearsed monologue. In this sense it is quite professional after all. Five thousand visitors had heard this recording by the end of 2007, and some of them may even have thought about what he said afterwards.

Technically, it is a very simple production. A high-quality microphone picks up his voice in a domestic room, and it is recorded with audio software. In all likelihood this recording is pre-produced, which means that Blunty3000 performed his tirade in one take, and uploaded it to his space on YouTube without any editing other than starting and stopping the tape. His behaviour to the microphone is quite personal, at least in the sense that the indignation is his own. He does not purport to speak for anybody but himself, and listeners can hold him personally responsible for his words and actions. Although formally it is YouTube which publishes the material, people who listen to this performance will relate to Blunty3000 as the editor, journalist and technician, all in one person. Blunty3000 has published a number of monologues on YouTube, and his confrontational style has earned him a long list of derogatory comments from other YouTube users.

YouTube demonstrates that people have acquired techniques for public expression that were previously restricted to professionals. In particular, people are learning how to present themselves effectively in a public setting, using microphones, cameras and editing software to great effect. Thousands of people are in the process of developing rhetorical techniques that may in effect become new media, since journalists and other media professionals will ultimately adopt many of them for programme purposes. This parasitic activity is demonstrated well by news websites that now put great value on discussion forums, personal video submissions and photographs taken by ordinary people with camera phones.

The crucial novelty that makes people into journalists or, better, micro-editorial production units is the easy access to what is in principle a public sphere. It is very easy to publish your stuff on the internet. Maybe nobody bothers to listen, but you can in any case make yourself available.

Premature publishing

Young people in the 2000s are media savvy. They grow up with expressive interfaces such as microphones and cameras, not just loudspeakers and screens. Amateur publishing can also be found among music lovers, and many young people meddle with recording equipment, where they create more or less attention-worthy music. This can also consist of mash-ups, where people sample and edit works by other artists, and modify their original intentions for their own humorous or artistic purposes. If you are making a home movie you can import your favourite recorded music into the software and edit it to become a nice-sounding soundtrack. This craft has little or nothing to do with professional recording qualities.

On Acidplant, MySpace and other user-generated content sites, hundreds and thousands of files are accessible at a click. Most of these files can be thought of as demos, although professional artists use MySpace in particular as an advertising medium for their music. In the analogue era a demo tape was something that aspiring artists brought to a record company, and everybody knew it was of poor quality and would be re-recorded in a professional way if the record company was interested. Clearly the process of publishing music through file sharing and websites is parallel to the analogue demo-tape process, except that it is easier to produce the music with high quality and possible to publish it on a global level. Upload it to the internet, and it is there for everyone in the world to hear, in principle.

Steve Jones (2000:217) argues that ‘recording sound matters less and less, and distributing it matters more and more’ (see also Jones 2002). The next case study involves a teenager who makes a music recording at home and distributes it on Acidplanet. He composes a melody and lyrics, and he invites a group of friends to accompany him. This has been a typical teenage thing to do ever since Bob Dylan first inspired youngsters to write their own material in the early 1960s. The band is called God vs. the Internet, and they sing a song with religious undertones.

Track 7: Acidplanet: God us. the Internet, 2005 (0:48).

Yeah. Here we go.

May the circle be unbroken,

My bottle bye and bye,

I found Jesus taking all my troubles,

Now he’ll walk you side by side.

And I feel alright.

Together, together.

I feel just fine.

Oh Sweet Jesus.

Ha, ha, ha.

Again the production technique is very simple. Several microphones are rigged to pick up several sound sources in a controlled studio environment. There are perhaps four persons performing. A man sings vocals, somebody plays acoustic guitar, there is a synthesizer (perhaps overdubbed), a trumpet and a tambourine. The acoustic architecture is simple: it has slight reverberation that resembles a domestic room, like a den, a teenage bedroom, or perhaps an office. There are no professional production values in this recording, no real balancing or mixing, and very bad audio quality.

Nevertheless, the melody of ‘May the Circle be Unbroken’ is beautiful, and the trumpet sounds especially vulnerable. There is a certain helpless charm to the song. It seems like the band addresses other young people, who are presumably more relaxed and optimistic than the adults, and the combination of ironic distance and sincerity in the lyrics might indeed appeal to teenagers. At heart this song illustrates the amateur enthusiasm that finds regular expression on all kinds of user-generated sites. But with respect, the threshold for publication is low in this case.

Notice that on the web listeners can often talk back to the producers. In October 2006 the following comment was posted on God vs. the Internet’s area on Acidplanet by a person called Paul D. Richardson: ‘Sorry if this is harsh, but that was the worst thing I’ve ever heard. I had to turn my speakers right up just to hear it, and when I did what I heard would have made the blues masters roll in the grave.’

The BBC’s acoustic authority

Now there will be a stark contrast to amateur journalism and amateur music. The professional productions of broadcasters and the music industry have been under siege by the internet since the early 1990s (there are many analyses of this convergence; see for example Lowe and Jauert 2005; Leandros 2006; Kretschmer et al. 2001). Most notably, their traditional forms are being challenged by the amateur practices I have just described. The problem is that the internet’s platforms are radically more interactive than the recording and broadcasting media, and a hundred years of asymmetrical cultural techniques have to be redirected.

Can public service broadcasting still offer something that is exclusive? It seems that truly professional sound journalism is the only thing that public broadcasting services still serve up as an exclusive product. For many decades public service broadcasting was the hallmark of quality journalism in Western countries. And when it comes to sound media, the stamp of quality was the compact news bulletin, investigative reportage, dramatic documentary programmes, and not least expensive programme formats such as radio plays (which you will never find on the internet other than those from radio stations). High-end radio production gave public service broadcasting an authoritative presence in the public life of the West, and it continues on the internet (Jauert and Lowe 2005).

If you enter the BBC’s huge internet portal looking for high-quality radio programmes, you will be satisfied. The next case study is from BBC Radio 4, which brands itself as ‘intelligent speech’. It is a thirty-minute science programme called ‘Acoustic Shadows’, which deals with the varied art of acoustic design. The blurb on the website reads: ‘From the most reverberant room in the world to a chamber where sounds die the moment they almost leave your mouth, Robert Sandall takes a journey into the world of acoustics — its origins, its people and some of its amazing soundscapes. ‘When it comes to production values this programme is dramatically different from Blunty3000 and God vs. the Internet.

Track 8: BBC Radio Four: Acoustic Shadows, 2004 (2:02).

[Recordings of concert hall acoustics]

[Car door slams] – Okay, we’re pretty near the Indian Hill site now, we’ve

driven about two hours from San Diego, we’re out in the middle of the

desert. It’s hot. Watch out for rattlesnakes!

[Acoustic guitar — Ry Cooder style]

– Steve Waller is a sound explorer in a literal sense. His field of research is

the rapidly growing one of acoustic archaeology, which involves him trav

elling the world studying the connection between ancient rock and cave

art and acoustics. Before they got the paints out Steve believes our ances

tors selected the sites they wanted to decorate for their potential as natural

echo chambers, a clear case of sound before vision.

– We’re standing at the bottom of this mountain that’s made out of basically house-size boulders. And in it is a fire-blackened cave that has Indian pictographs, which are basically painted rock art.

– Steve, we’re heading for that small opening a hundred feet further up?

– Oh, yeah, it’s one spot which they chose to decorate. That is where the

echo’s coming from. [Dahh!] It’s as if the sound is coming right out of the

mouth of that cave. If you think back to when the ancient peoples thought

that echoes were due to spirits speaking back, you can see that it’s as if the

rock is speaking to you, as if voices are calling out of the rock, and they’re

calling out right from that place on the side of the hill where they chose

to decorate. [Dahh!]

The programme is concerned with acoustic archaeology, and the reporter Robert Sandall has made recordings of indoors and outdoors acoustics which he uses rhetorically to demonstrate what acoustic archaeology is about. The listeners can sense the rocks and cliffs that the speakers walk between, and the reverberant ‘dahh!’ informs us just as efficiently about the topic as the speech by the two men.

The programme is post-produced, with careful editing together of three different types of sounds: the voice-over and outdoors speech; the environmental sounds of cars, walking, shouting in a reverberant space; and the guitar music. Seventy years of competence-building in radio journalism lies behind this reportage, and we can hear the accumulated skills of creating a seamless, well-dramatized entity out of a series of raw materials (see for example Herbert 2000: 193ff.; and McLeish 1999: 257).

When it comes to the protagonists’ way of speaking this reportage also conforms perfectly to the demands of classical radio journalism. The BBC journalist reads from a well-prepared script, and in this type of address the speaker is expected to function as a skillful animator of the facts and explanations contained in the script. Although the reading should be vivid and lively, there should be as few traces of the journalist’s personality as possible. In contrast, the interviewee should sound as if he is improvising his speech in a personal and intimate way, since he is after all not a professional journalist. But still, the behaviour of the interviewee should be harmonized with journalist’s speech. At the end of the excerpt, when Waller says that it is as if ‘voices are calling out of the rock’, he speaks with exactly the kind of enthusiasm that the journalist needs to complement his own reading parts. Both speakers were well aware that what they said at the microphone would be edited before it was put on air, and this made their behaviour relaxed and quite natural-sounding.

There are two professional qualities here that are often lacking in amateur recordings on the internet: the smooth, inaudible editing of multiple strands of sound, and the seemingly effortless and highly informative speech. My point is that high-quality reportage is the hallmark of public service institutions on the internet, while user-published content is made with much less sophisticated production techniques, and would not readily be taken up by public service institutions. This is not a surprising division of labour. The big broadcasting institutions have created professional journalism for over seventy years, and this long-standing tradition keeps journalism from truly resembling the amateur initiatives on the internet.

Public service broadcasting is often seen as a protector of democratic values and as the narrator of personal and social stories with relevance for the citizens (Carpentier 2005: 208;Winston 2005: 25Iff.;Williams [1975] 1990: 32ff). In having such important functions journalism rises above the communication that ordinary citizens can affect between themselves. Journalists work in a well-defined profession with trade unions and interest organizations, and they possess complex expressive skills involving writing, camera work, styles of speaking and moving around, editing, checking sources, complying with ethical guidelines etc In a cultural sense public service broadcasting will always consist of one-way communication, with a centralized editorial organization distributing their carefully made product to the masses. The BBC’s website demonstrates that this asymmetrical relationship works fine also on the internet.

Podcast frenzy!

In a matter of a few years from 2005, podcasting has become a standard option for listeners (Levy 2006: 227ff). By clicking on the ‘subscribe button on a website, listeners can regularly receive fresh instalments of their chosen audio or video programmes. I will go into the technical details of podcasting in a later section- here I will attend to the production values of podcasting.

The next case study is from a podcast-only service called www.twit.tv (the acronym stands for ‘This Week in Technology’). The company produces its own original podcasts, and this makes it different from many of the podcasting services which distribute standard radio or television programmes on just another platform. I have selected a podcast that TWIT made about an event called the Podcast Expo in California 2006; it was made during the buzz and expectations of the big conference, and everybody is wandering around, testing, buying and selling podcast products.

There is an upbeat rock jingle at the beginning, and professional voices read the headings in a neutral style, sounding mechanical in much the same way as the voices that say ‘Mind the gap’ at underground stations. ‘Netcasts you love (a man). From people you trust (a woman).This is twit (a man-woman duet) . This soulless but informative way of speaking is a classical feature of American-style broadcasting. There are also several sponsored messages and when the actual programme begins it resembles talk radio quite a lot. The similarity to the production values of American commercial radio is quite striking.

Track 9: This Week in Tech: Podcast Expo, 2006 (2:31).

– And we’re live at Podcast Expo [-Yoohoo], I could say Netcast Expo, Doug Kay is here from IT Conversations, he’s gonna hand his tiara oft to me a tittle later on. [- Absolutely] Last year’s podcast person of the^ year. And if you should fail to, it could, succeed in your duties, you 11 be, III be runner up [- Okav, thank you, yes] -Actually, Doug has a big announcement, so we’ll get to that in just a second. Also with me Steve Gibson, another TWIT from Security now and GRC.com. Sitting next to Steve Gibson, the great Scott Warren from Mac Great Weekly in the Eyelifezone [- Hi everybody], he’s also a great aperture expert, aperturetncks.com and pod-castmgtricks.com. What we’re gonna do today is talk to a lot of podcast-ers as many as we can in half an hour before they take this stage away from us Podcast Expo is, this is the gathering of the tribes tor podcasting, the second year we’ve done it, about 25 hundred people, we’ve taken over a small part of the Ontario Convention Center, a lot of booths showing podcast software, podcast hardware. Broadcasters General Store is here and thanks to them we’ve got audio on this podcast, they let us [— Which is really handy for a podcast]. It certainly makes a difference, they let us their Alesis Multimix 8 Firewire.

TWIT produces mainly live-on-tape events, which are cheap and simple to create. In this case there is a row of industry men on stage, they are introduced by the host, and the host talks to them all in the course of the programme. This is an example of resounding studio acoustics. Several microphones are rigged on a stage, and the performance takes place in front of a live audience. The programme is mixed to pick up the performers and the audience reactions, and also to convey the size of the hall and its atmospherics. It all sounds authentically like the Ontario Convention Center in Los Angeles.

Podcasting is not a live medium like web radio, and among other things this implies that the raw material for a podcast can be heavily edited before it is launched to the public. Since the producers are well aware of this while taping the show, the mood of podcast programmes can be more relaxed and happy-go-lucky than traditional radio. But there are lots of similarities with radio, as I have already suggested. For example, podcasting mainly communicates in the form of twenty- to thirty-minute programmes, which happens to be the typical length of a traditional radio programme. Some podcasters make three- or four-minute installments, which is the typical length of a radio commentary piece.

Listening to the message of the TWIT podcast, I have to say that it sounds quite partisan. By reporting so enthusiastically from the Podcast Expo, TWIT promotes its own platform every minute of the way. The speakers want recognition of podcasting as a medium, and this podcast is a good example of the intimate connection between equipment manufacturers and editorial production. This is not critical journalism, this is an expression of a common interest in expanding the market that is quite typical of new internet media. The pod-casters try to sell equipment and programmes, and perhaps even establish a new medium with social practices of its own.

The Podcast Expo illustrates the driving forces of technological innovation in the media. The modern mass media are built on competitive lab experiments in the military-industrial complex and commercial enterprises, and the motivation is basically the same in the podcast industry. There is an intense pursuit of better functionality and greater efficiency and more diverse areas of use. Companies such as Microsoft, Apple, Nokia and Google try to create the next killer application, like the iPod was. You can ask who will win the competition, but the truth is that the competition will never end; it will only change into being about something else.

I will end this section on a critical note. It is important to consider that the optimistic moods of advertisers, PR companies and the broadcasting stations may be purposefully unrealistic. In the article ‘The Mythos of the Electronic Revolution’, James Carey and John Quirk argue that there is an idealizing rhetoric embedded in the very fabric of electronic communication, which they call ‘the rhetoric of the electrical sublime’. This is, they say, an ethos ‘that identifies electricity and electrical power, electronics and cybernetics, computers and information with a new birth of community, decentralization, ecological balance, and social harmony’ (Carey and Quirk 1989:114). In their view technological life includes a clever ideological and commercial staging of roles for people to believe in, where the various appliances are seen as necessary for succeeding in one’s life involvements. Carey and Quirk refer to this as an ethos that goes like this: ‘Everyman a prophet with his own machine to keep him in control’ (ibid.: 117).

The computer sound medium, 2008

Now I will turn to a more precise analysis of the medium I am talking about: the ‘computer with internet’ medium. Regarding sound production, the computer medium is quite symmetrical in a technical sense. It is truly the same equipment that is being used by the important BBC journalists and the amateur musicians. Both of them can, for example, edit and mix their production on their laptop in the evening. Since all parties can in principle publish and distribute messages, it is difficult to say that it is a linear medium with production at one end and reception at the other.

But although the medium is quite symmetrical in access and opportunities, there is a big difference between the professional training of journalists and musicians, on the one hand, and the lack of it among ordinary users, on the other. As I have suggested earlier in the chapter, we can hear this by comparing the BBC’s ‘Acoustic Shadows’ with the shouting monologue by Blunty3000 on YouTube.

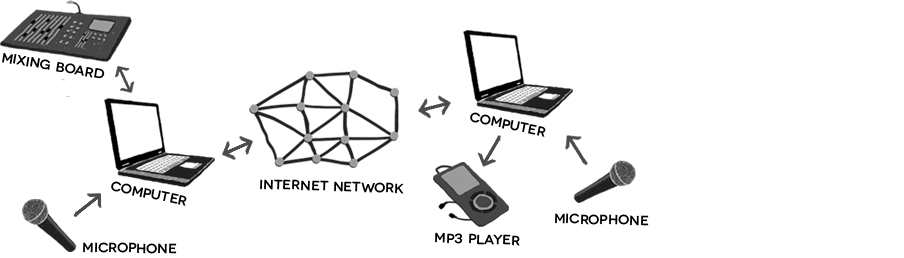

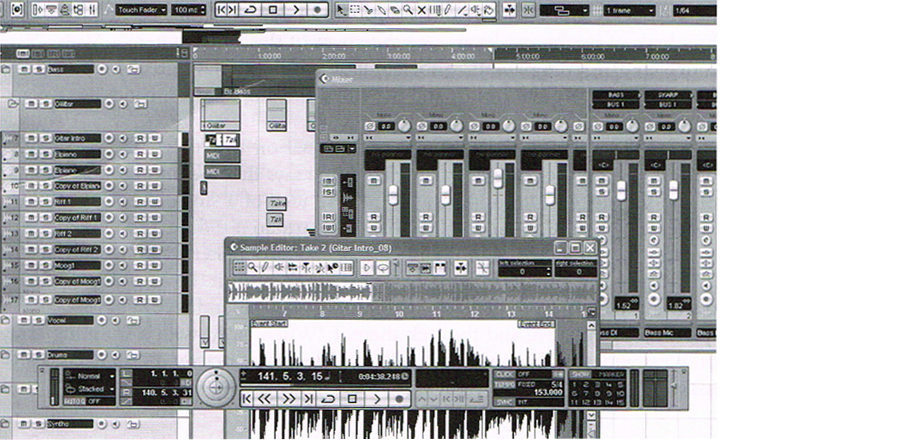

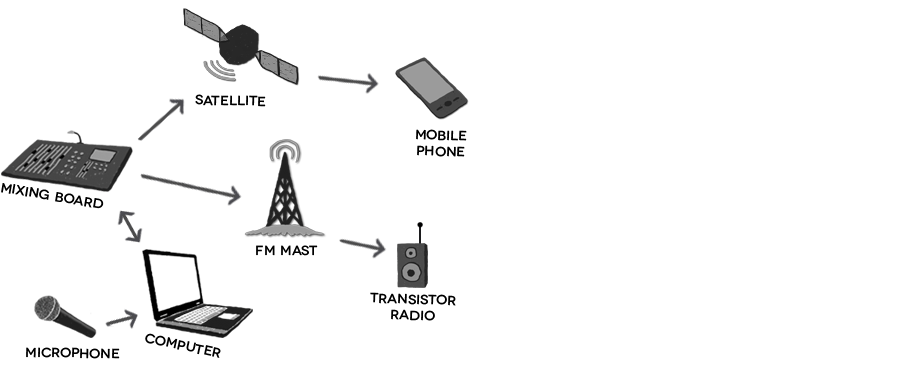

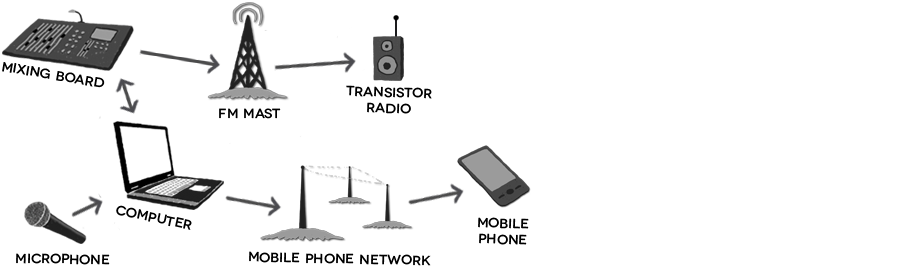

Figure 2.2 shows the technical environment of sound communication on the internet. The mixing board at the production end symbolizes the great creative control that producers and journalists still typically have in comparison with listeners. The mp3 player at the reception end symbolizes the flexible ways in which listeners can use the sounds from the internet (and computer). Notice that for both parties almost all the vital functions are contained on the computer in the form of software. The figure shows that there are essentially two platforms: the personal computer and the network between those computers. I have argued that, when it is hooked to the internet, the computer is a medium of live distribution. But the issue is more complex. The computer has a storage and playback feature that always works, whether there is a connection to the internet or not, and this is simply the computer itself. In addition there is the live connection that can be turned on or shut off by the user.

The computer is sometimes called an Überbox, which refers to its tendency to contain all kinds of other media. And, indeed, all the traditional interfaces of sound media are clustered around the computer, for example mixing boards, sound-proof studios, LP turntables, video cameras, microphones and synthesizers, and all these familiar interfaces could have been drawn up in the figure. This clustering is possible because the computer platform is what Alan Turing called a ‘universal computing machine’ (Rheingold [1985] 2000: 45ff.) that can run any arbitrary but well-formed sequence of instructions. It can, for example, encode and decode written messages, or sample and store photos, sound and video. Whatever it is, the computer can process it according to its basic algorithms, which rely on the numbers 0 and 1 in endless combinations. The rich acoustic and visual experiments at the computer are translated into binary signals during production and are converted back to the human realm during playback.

The digital signal carrier is so miniaturized and blackboxed compared to analogue signal carriers such as the LP that it almost seems to not exist as a material fact at all (Simpson 1998). It can be contained in all kinds of microchip devices; and it seems completely immaterial apart from the file icons that pop up on the screen when, for example, you put a memory chip in the USB port.

The most striking feature of the double platform of computers and the internet is the web of connections that it offers. It creates access between all parties that have a modem or broadband connection. Remember that the internet is based on the same principles as telephony, except that it does not transfer analogue voices, but digital information. That old network has been in operation in most countries for over a hundred years, and the wires are well established in the home. This feature to some extent explains the rapid rise of the internet. Users can also hook up to internet providers through mains electricity, satellite dishes or cable networks.

The processing capacity of the computer (with internet connection) can be considered a public resource. When you don’t use your processing power it goes to waste since, for every second, hour and day that it lies inactive, it could have been used for some calculating purpose. The processing capacity could have been lent out at night – for example, to scientists who could use it to analyse raw data from radio telescopes that scan outer space for signs of intelligent life (see http://setiathome.berkeley.edu). Some people download music and films and podcasts all through the night and stockpile enormous amounts of cultural products that they will never consume in full, but which nevertheless serves the purpose of not letting their time-bound information resource go to waste.

I have already discussed the rhetorical potentials of web radio and podcasting. Here I will describe the two new platforms in comparison with traditional broadcast radio, in order to get their special features across as clearly as possible. Web radio and podcasting can be considered sub-platforms in the great multimedium which I call ‘computer with internet connection’. However, since this mother medium has such a stable presence, the sub-platforms can for all practical purposes be treated as self-standing media platforms (just like email software, web browsers and other appliances).

Audio streaming was a groundbreaking live technology for the internet (Priestman 2002). Notice that this is not the same as downloading, since no files are transferred to the computer. The audio streaming player made it possible to listen to the sound while receiving it, and in effect this introduced radio on the internet. As I have already noted, all websites rely on visual guidance for the listener, and web radio is no exception. The listener must search the web to find web radio stations, and the streaming feature is packaged in a rich visual environment of news, schedule information, contact information, and so on. Nevertheless, web radio re-creates that fundamental quality of broadcasting which is called ‘live at the point of transmission’ (Ellis 2000; Hendy 2000), albeit in a telephonic network instead of through terrestrial transmission. Although there is a buffering process between the streaming servers and the listener’s computer that can delay the signal by up to ten seconds, web radio in effect transfers sound in the same temporal manner that FM and AM radio has always done (Priestman 2002: 9). Web radio is a cheap form of publishing and distributing sound, and it has greatly lowered the threshold for establishing new editorial outlets. Services can, for example, be made without large initial investments for small groups scattered around the world (Coyle 2000). The internet has become the main delivery system for thousands of web-only radio operators and an important supplementary platform for practically all radio broadcasters.

In contrast to web radio, podcasting is not a live medium, because the message has to be completed in every facet before it is published and distributed. There is no streaming process; instead, the file is automatically downloaded to the computer, and it must be actively deleted by the user. Because podcasting relies on downloading, nobody expects the podcast programme to be interrupted, for example, by breaking news. The podcast platform has no readiness to respond to current events, except that of course a new installment can be published sooner than originally planned if some pressing event makes it opportune.

The subscription feature of podcasting is important to notice, since it is quite different from web radio’s live streaming. The listeners get their radio in the mail, so to speak. This is very different from traditional radio, which has always been characterized by the here and now of the public sphere. The listener receives new programmes on a regular basis, for example once a week, and can bring the recordings out into their everyday surroundings and play them back on the iPod (Berry 2006). All the major radio stations offer this service for most of their programmes, and it has led to an increase in listening to talk and information programmes among people who would previously not listen much to the radio. Notice that mobile listening to podcasting contrasts with the way in which people listen to streaming audio, where (in 2008 at least) they are more strictly bound to the stationary computer or the laptop. Typically, the podcast user will listen while doing something else, just like radio programmes and music have always been enjoyed.

Meet the pirate

File sharing has led to great innovations in the art of listening – innovations that keep us in control of our music (Hacker 2000). Admittedly these innovations have taken place in dubious ways. Peer-to-peer networks have long challenged the music industry by allowing music to be shared without compensation to the rights holders, and without any sales of CDs or other physical media by the record companies. This alternative music industry was introduced with sites such as Napster in the late 1990s and the Pirate Bay in the 2000s (for elaboration, see Alderman 2001; Sterne 2006; Rodman and Vanderdonckt 2006).

Music lovers can make playlists for their Walkman or iPod, just like people made mixed tapes to play in the car in the analogue era. People’s playlists typically have a single song focus rather than in-depth attention to whole albums. This also goes for podcasting, where you select your favourite shows instead of listening to a live flow. This reduces the producers’ and artists’ control of the role of the individual items in a larger album context. Playlists can be organized by genre, year of release and many other variables that give the music lover greater control over their act of listening than ever before.

Since there is so much music on offer on the internet, the listener can in principle cherry-pick their music and compile the perfect record collection. Once the music is downloaded to the computer it can be organized in an audio library. These activities have increased what Paddy Scannell calls the ‘personalization of experience’. He argues that the media are ‘something that individuals can now increasingly manage and manipulate themselves through new everyday technologies of self-expression and communication’ (Scannell 2005: 141).

However, the cherry-picking by music lovers is not something new. As the historical part of this book will show, a highly sophisticated culture of listening to records had developed already by the 1930s, and it was strengthened with the arrival of stereo music on LP in the 1960s.This culture lives on among the LP and CD lovers who still listen to a whole album in one concentrated act of listening, and who have a solemn reverence for their albums.

In the context of file sharing on the internet, music lovers can build a really big music collection at low cost. This is what Jacques Attali (1985: 101) calls ‘stockpiling’. People buy more records than they can listen to, and the pirate most definitely downloads more music than he can listen to. The storage capacity of computers in the late 2000s is great, and avid music lovers can have 20,000 to 30,000 songs in their file cabinet. Presuming that an average CD holds approximately fifteen songs, this equals something like 1,300 to 2,000 CDs. Although people basically create their own private record collections, they can of course share them with anonymous others through file sharing software. The music collection is a part of the public domain for as long as the user makes it available.

Some music lovers relate to music less as an expensive and fragile commodity and more as a huge standing resource. Some feel that it is so easy to download music that the actual file is not worth caring too much about. There is no need to build up a personal collection of files if you can serve yourself online at any time, the argument goes.

The search engines of the internet bring sound recordings to hand more easily than ever before in the 130 years of sound media. Amazon and eBay are places to look for CDs to buy, while iTunes and other companies present legal music. Of course, thousands of pirate sites distribute music to anybody for free. The internet functions as a standing reserve of sound, or, more precisely, of references for sound, that the listener can choose to launch or download. Websites such as Allmusic or Rhapsody have plenty of background information about songs and artists, and there are websites specializing in transcriptions of pop lyrics. Compared to the information that can be supplied on a CD cover, the internet has a radical potential for informing the user about the cultural and historical setting of the music they listen to. Very often people search in an open and curious way, limited only by their perseverance in pursuing their interests. Notice that a search can also be conducted through visual cues on a website – pictures of artists, logos for radio stations and other graphical material. Often a quick glance tells you what you need to know.

Sound browsing is also possible. Allmusic provides excerpts of 5.5 million songs which can be chosen from standard browse and search procedures, so people can listen to a thirty-second snippet and evaluate the music before they buy or download it. Notice that this is not really an auditory search, since this would imply that the user enters an excerpt of, for example, a guitar sound, and the search engine would find all the songs with the same type of guitar sound. But the Allmusic monitor after all means that you can steer your search for musical pleasures by attending to the actual music, and not to written recommendations or information that the graphical interface alone can supply.

The computer is a miracle

It is difficult for ordinary people to learn how the computer and internet actually work. You are confident that you could explain it comprehensively if you had the time and money to educate yourself and study it at length, but since that is not possible, or not in your interest, you have to rely on the functionalities by default.

Rather than interrogating it ourselves, we are likely just to accept it all as a functional fact of life. There is a tension in this way of living with things, an uneasy or hesitant or even reluctant acceptance of the great functionalities and increased opportunities. This is trust in technology. It does not come about by conscious thought processes in every instance of contact. On the contrary, it comes about because of withdrawal from explicit thematization (Nyre 2007b). Paddy Scannell describes this notion of habituation in the context of broadcasting:

The language used to describe the invention of radio first and, later, television expressed over and over again a sense of wonder at them as marvelous things, miracles of modern science. Their magic has not vanished. It has simply been absorbed, matter-of-factly, into the fabric of ordinary daily life.

(Scannell 1996: 21)

People don’t think much about the computer’s strangeness, and don’t have time to study it in full technical detail. For most people the incomprehensible sediments into a habit and its complexity vanishes. Alfred Schutz (1970: 247) writes: ‘The miracle of all miracles is that the genuine miracles become to us an everyday occurrence.’

3. Synthetic music – Digital recording in great detail

Synthetic sound is all around. Even grandmothers listen to techno beats and weird sounds of synths, samplers and computers. Two innovations in particular have made these technological sounds possible, namely multitrack editing and the digital generation of sounds. These intricate cultural techniques have been around since the 1970s, but with the computer they have become a mainstream phenomenon (and only then, in my perspective, does a technique become truly interesting).

Three case studies will be presented, all of which in different ways demonstrate the hyper-technological character of modern music. First I will analyse a densely multitracked rock composition by the group haltKarl from 2007 and present two versions from different stages of the production process. Secondly, I analyse a completely synthetic techno beat by Autechre from 1995 where it sounds as if no microphones have been used at all. Finally I will analyse a passionate crooning performance by Beth Gibbons and Portishead from 1994. Her performance is just as human as the human voice can be, despite its being embedded in a dense flow of sampled sounds and drum machine beats.

The synthetic media landscape

Westerners in the 2000s are a media-sawy people. It seems that nothing can surprise us when it comes to hearing and understanding recorded sounds (and images). People can hear sounds from outer space, sounds from inside an ant hill, and sounds from the volcanic inferno of the earth’s core. In the context of visual media, we have seen the insides of a womb and the hurricanes on Jupiter in colour. Impressive though these representations are, they are strictly documentary. People are also used to another type of media experience: animations in sound and images that are created entirely inside the technologies, and which nobody would mistake for something that exists outside the media. When dinosaurs charge down the road in Jurassic Park (1993) there is no doubt that the images are non-documentary, and the same is the case for TV promos, commercials and programme intros that are often highly advanced when it comes to graphical effects. This type of animated reference is often used for entertainment and aesthetic effect, where there is no moral imperative to represent the world in a realistic manner. However, there is heated discussion about ethical problems in digital animation, since now the technical possibilities for manipulation are almost limitless (Kerckhove 1995; Gitlin 2002: 7Iff.).

When describing the synthetic production of music I want first to connect to an ongoing cultural process that parallels the visual animations of TV and film. American and European music lovers enjoy the products of an industry with a joint creative history that goes all the way back to the cylinder phonograph in the late nineteenth century. This means that there are well-developed aesthetic sensibilities among the general public, and during the last three decades these sensibilities have shifted towards greater acceptance of technological sounds. Hip-hop, techno music, electronica – whatever trademark is put on the music, it has none of the acoustics of the concert hall, but all of the acoustics of the computer. These techniques of production have become influential on people’s tastes in general, and are used in commercials, on film soundtracks, in computer games, and so on. The music lover has turned towards textures and timbres, and considers them enjoyable in their own right.

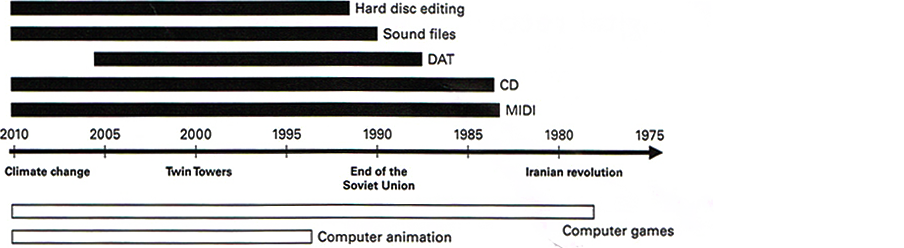

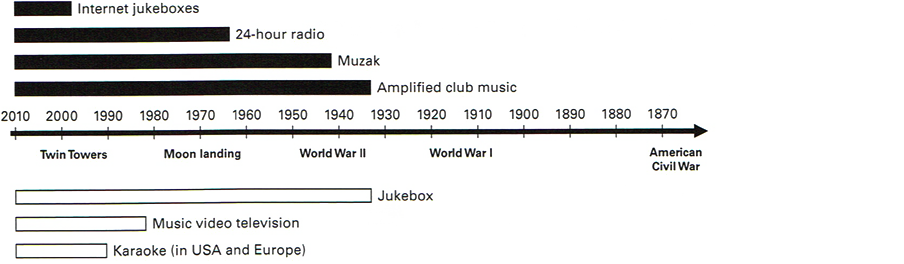

Figure 3.1 lists the main platforms that are necessary for the creation of synthetic music. There is clearly a thematic overlap with the platforms that were discussed in chapter 2, for example regarding file sharing and mp3, but this chapter focuses more strictly on high-quality music production. Underneath the timeline I have listed visual animation media – computer games and animation formats based on software such as GIF, QuickTime, Shockwave and Flash. These visual animations can be accessed on the internet and played on a computer. It is instructive to start my discussion of synthetic sound production on the background of visual animation. To create the illusion of movement, an image is displayed on the computer screen, then quickly replaced by a new image that is similar to the previous image, but shifted slightly. Each image can be constructed entirely on the computer or be a montage of real footage and animation. This technique is identical to the way in which the illusion of movement is achieved with traditional television and motion pictures, except that every pixel must be plotted by a programmer instead of being automatically registered by a camera lens. In principle, computer sound is designed just like the computer animation of images.

One of the really big changes in music recording happened quite recently. During the 1980s the introduction of the CD started a slow but ultimately complete replacement of analogue equipment. From the 1990s there was file sharing, and people started getting used to music in the form of computer files. The change created fruitful conditions for the development of synthetic techniques.

Audio editing software made it possible to manipulate the sound with graphical interfaces, particularly in the software layout as it appears on the screen. Cut and paste editing was a very important innovation, and it started influencing music production from the early 1990s. Before that it had become widespread in word processing software such as WordPerfect and Word (Manovitch 2001).

The MIDI standard for programming of music scores and instructions was the first commercially viable digital technology for synthetic sound creation in the early 1980s. MIDI stands for ‘musical instrument digital interface’, and this protocol enables items of electronic music equipment to communicate and synchronize signals with each other (Chanan 1995: 161, 357). In combination with samples of instrument sounds, a given MIDI composition can be played back in any type of sound, for example, the violin, the guitar sound or falsetto singing. Notice also that computer games such as Pac-Man and other stand-alone devices had their own sound-generating principles before the advert of MIDI.

Hard-working rockers

Before I describe digital recording in detail, I will remind you that recorded music is still a physical thing, despite its fugitive digital existence. Recording ‘turned the performance of music into a material object, something you could hold in your hand, which could be bought and sold’, argues Michael Chanan (1995: 7). In addition to the potential for making money, recording allowed musicians to hear themselves as other people would hear them. They could listen very carefully to several takes before they decided which was the best one, which they then released to the public. During the decades artists have cultivated this technique, and it is now a completely integral part of record production, as can be seen by the central location of monitor loudspeakers in the control room. The activity can be called analytic listening.

In this section I will attend to the way analytic listening influences the recording process, and my point is that it is crucial to the painstakingly careful construction of sounds, bit by bit, sample by sample, instrument part by instrument part. Musical events are first recorded straight through, and afterwards they are altered and combined with other musical events in the progress of editing, to construct the desired musical rhythms, melodies and harmonies. All the time the producers listen carefully to the sound and discuss it among themselves. Layer upon layer can be added or removed according to the producers’ changing creative vision. Even low-budget recording sessions in an attic involve a tremendous modification and manipulation of the musical sounds.

Track 10 is from a Norwegian recording in process. The group is called haltKarl, and since it has not yet released any CDs it is completely unknown to the wider public. The band will probably aspire to national fame sometime in the future. This song has actually been under development for around five years, and we hear two versions: the professional version from 2007 and a demo version from 2005.

Track 10: haltKarl: Almost GUIs, 2007 and 2005 (1:51).

Both my lungs are spoken for

Breathing water in through the pores

Hormones might get the best of me

Black men might just have bigger feet

All my girls got the same disease

And all my girls want a better deal

All my girls cry

All my girls go

Under water I can hear them.

The music is in rock style; it sounds rather like heavy metal with beach harmonies, or like a mix of the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Beach Boys. The three-man band plays guitars, bass, drums and synths, sing solo vocals and harmonies, and use all kinds of digital effects.

The sound is highly controlled, which is a result of the slow composition method that has been used. It is as far from a live performance as one can get, although it actually sounds much like a live performance. The clarity and simplicity of the sound belies the immense depth of layers in the song and its production process. The band owns a large array of stomp-box effects for the guitar and bass, software plug-ins, outboard synthesizers and effect processors that can modify the signal from any type of source into whatever sound is wanted. haltKarl is exploiting the powerful computer processing capabilities of relatively cheap modern-day computers to the full.

Regarding its production technique, ‘Almost Gills’ has an interesting chronology which I will go into in some detail. The song has been recorded twice, in two completely different versions that nevertheless sound much the same at first hearing. haltKarl is a determined band, and in 2005 its members were satisfied with the melody, lyrics, harmonies and detailed instrument arrangements, but not with the production qualities of the song. With the structure of the song set in stone, they started preparing a new, professional on, where all parts, instrumental as well as vocal, were rerecorded. On loundtrack we first hear the new but still unmixed version from 2007. It recorded in a semi-professional studio with a relatively short production od, in contrast to the 2005 version, which has a far less professional sound was recorded in basements, cabins, living rooms and even bedrooms over a number of years.

There are several reasons for analysing the strategies of an unknown rock group from Bergen. The production techniques used are now so typical as to be almost the industry norm, despite the fact that they are extremely time-consuming. The slow construction of a song, layer by layer, is just as common in rock or hip-hop or techno, among struggling artists at the home computer as well as the big established acts in expensive recording studios such as the Record Plant in Los Angeles. The process of improving the sound can go on for months or years before the artists are satisfied. The album OK Computer by Radiohead (1997) is a case in point. In fact, this construction process is now so widespread that it is the starting point for the cultural perception of music not just among the musicians themselves, but also among ordinary people. In other words, the entire public is well skilled in enjoying sound with these highly complex characteristics.

Techno acoustics

The next case study will relate to acoustic characteristics. Artists design the acoustic properties of their recordings very carefully, and this can be called the acoustic architecture of sound media. In chapter 1 quoted Ross Snyder ([1966] 1979: 350) referring to musicians as architects of a spatial habitat ‘in which contemporary man will live and move and have his being’.

Acoustic architecture is intuitively understandable as relevant to concert recordings and other cases where an actual space is picked up by microphones. But there are more difficult examples. The electric guitar and the Hammond organ produce sound via internal electronics; so where are these sounds located? It would be strange to say that the sounds of the electric guitar resonate somewhere inside the instrument, as if it were just like a saxophone or a drum. This problem of reference became more pronounced with the synthesizer and its programming of tone-generators. Sounds then became internal to the technology in the simple sense that they did not resonate in a real room and were not picked up by microphones. They were created wholly on the inside of the equipment and sent directly to the tape or the loudspeaker.

The music of the German group Kraftwerk is a good example of at least partly synthetic music. Mark Cunningham (1998: 281) comments on this 1980s techno sound: ‘If there was a shared emphasis among the varied styles thrown into the charts from the early to mid-Eighties it was one of unnatural sounds, created electronically by sequencers, drum machines, synthesizers and the advent of sampling.’ Few if any acoustical instruments are played on Kraftwerk’s albums; the only sounds that are definitely from the world outside digital construction are the voices of the singers.

‘Dael’ (1995) by the British duo Autechre is an example with fully synthetic acoustics. This English band is well known to techno freaks but virtually unknown beyond their hardcore audience.

Track 11: Autechre: Dael, 1995 (1:09).

[No lyrics]

It creates a very precise sound which is ‘written’ in layers of rhythmic elements speeding up and slowing down, with a dark melody behind. There are strange modulations that sound like a zipper being drawn and a repetitive rhythm, and the overall effect is metallic, sharp and cold. None of the sounds are analogue, and there are no vocals or analogue instruments such as a guitar or trumpet. Notice that the analysis of what the band has done to create the sound can only be based on speculation, since there are so many ways to make music with digital software (and MIDI plug-ins). It is really impossible for anyone to establish the production process of this type of music.

This has something to do with the fact that synths and MIDI signals have a purely technological acoustics; and this in turn implies that the recognition of spaces and sounds among music lovers is restricted to their knowledge of synthetic instruments. Notice that MIDI carries instructions written in a computer language that all modern synthesizers, drum machines and other digital processors can understand (Honeybone et al. 1995: 23). The proliferation of MIDI implies that popular music in general has ventured into a synthetic timbre-management. The activities at the mixing board and the computer can now be considered as important as the sounds of traditional musical instruments.

This development has concerned music lovers for several decades already. In 1990 Andrew Goodwin claimed that, with sampling and other digital developments, the authority of the artistic statement has been reduced: ‘The most significant result of the recent innovations in pop production lies in the progressive removal of any immanent criteria for distinguishing between human and automated performance. Associated with this there is of course a crisis of authorship’ (1990: 263). As I have suggested, it is difficult to identify the performers, and to point out what their musical accomplishments actually consist of. Goodwin claimed that sequencing and sampling technologies have cast such doubts upon our knowledge about just who is (or is not) playing what that some bands place comments such as ‘no sequencers’ on album covers to retain their status as ‘real’ musicians (ibid.: 268).

In the late 2000s it is another story altogether. Music lovers are now so used to the synthetic techniques that very few would consider them unreal or interior to musical sounds picked up with microphones in the traditional way. Indeed, the members of Autechre are not at all afraid that their status as musicians will be compromised by the synthetic way of playing music. On the contrary, their reputation in the techno community is rock solid because of the seriousness with which they approach the art of computer music.

The passionate crooner

A third fundamental feature of recorded sound, along with space and time characteristics, is the personality of the artist. In the old days, with singers such as Edith Piaf and Vera Lynn, there was a strong emotional connection between listeners and artists. But can listeners relate to persons in such an intense way when the music is so marked by synthetics and computerization?

My next case study is a trip-hop song by Portishead from 1994. Portishead is an English band well known to lovers of contemporary Western pop and rock. They were part of the Bristol sound, named after the city in the west of England where such bands as Massive Attack originated. It was characterized by ‘minimalistic arrangements, dub-influenced low-frequency basslines, samples of jazz riffs, keyboard lines or movie soundtracks, and drum loops -“breakbeats” characteristic of hip hop and rap from the ghettos of American cities during the 1970s and 1980s’ (Connell and Gibson 2003:100). In the song ‘Glory Box’, the lead singer Beth Gibbons makes her voice stand out as particularly human against a background that is particularly technological.

Track 12: Portishead: Glory Box, 1994 (1:03).

I’m so tired, of playing

Playing with this bow and arrow

Gonna give my heart away

Leave it to the other girls to play

For I’ve been a temptress too long

Just …

Give me a reason to love you

Give me a reason to be a woman

I just wanna be a woman.

This is a lush electronic sound. The band creates a dense flow of drums, bass, synths and electric guitars, and there is an LP sound effect that makes it seen as if the music is being played on a turntable. There is also a lingering reference to several other compositions, for example Tchaikovsky’s ‘Swan Lake’ and the 1970s pop song ‘Daydream’ by Franck Pourcel’s Orchestra. This goes to show that, although ‘Glory Box’ may sound very modern and alternative because of its technical aspects, the song follows a long melodic tradition. Notice that ‘Glory Box’ contains a sample from Isaac Hayes’s ‘Ike’s Rap III’ (liner notes on the CD).This is the most direct way in which Portishead refers to other musical works, since a sample is after all a little piece of a recording made by another artist (for implications of sampling, see Chanan 1995: 161 and Goodwin 1990: 258ff.).The listener would have to be quite familiar with Isaac Hayes’s work to recognize the sample, though.

Beth Gibbons sings in a good voice, crooning just like pop artists have done since the 1930s (see chapter 9). As I have already suggested, she manages to sound like an especially vulnerable woman in this stark electronic setting. It is an outstanding case of a craft that appeared in the 1970s, where female singers such as Joni Mitchell and Kate Bush projected gentle human moods against a background of a complex rock production. By adding the LP sound Portishead signals a retrospective acknowledgement of this previous era in pop music history. My conclusion is simple: listeners can relate to singers in the digital age with as much trust as they did before. Listeners are likely to think of Beth Gibbons’s exclamation ‘I just wanna be a woman’ as an expression of her autobiographical frustrations as a woman.

However, a conservative music lover might argue that these hi-tech recordings are not as authentic as the old recordings of Edith Piaf or Louis Armstrong. Singers nowadays are assisted tremendously by voice technologies, such as modulating the voice to be in the right key, while in the past artists always had to be good to sound good. But if artists lose their credibility by manipulating their voices and putting them into a technological context, then there is very little credibility in modern music. Clearly, since the human voice can be modified just as easily as any other sound, it cannot be denied authentic qualities any more than other modified sounds. The alternative would be to suspend trust in absolutely all sounds recorded after approximately 1970, since have all been manipulated.

Among music lovers the traditional view has been that the human voice is untouchable. In the 1980s there was a certain pop design philosophy, practiced for example by the Human League, that allowed all sounds apart from the human voice to be synthetically created (Cunningham 1998: 291).

There is something extra valuable about the untouched voice, it seems. Basically, a voice is personal in the sense that friends and acquaintances can recognize it as belonging any more than other modified sounds. The alternative would be to suspend one’s trust in absolutely all sounds recorded after approximately 1970, since they have all been manipulated.

Among music lovers the traditional view has been that the human voice is untouchable. In the 1980s there was a certain pop design philosophy, practised for example by the Human League, that allowed all sounds apart from the human voice to be synthetically created (Cunningham 1998: 291).

There is something extra valuable about the untouched voice, it seems. Basically, a voice is personal in the sense that friends and acquaintances can recognize it as belonging to one unique individual among hundreds and thousands of other persons. In this way it points to a name, a set of personal characteristics, etc. To say that a voice is recorded means that people who know the person beforehand will recognize the recorded voice as belonging to that unique person. If the voice sounds alive and rough, with traces of whisky or drugs and the background of a nightclub coming through in the recording, the chances are that the artist will be felt to be authentically mediated. The human voice has an ethos of its own, an emotional, personal appeal that most musicians do not dare to disrupt. This conforms well to traditional ideas of’authenticity’ in pop and rock music.

Notice that, strictly speaking, a hi voice cannot be synthetically created. With a synthetic voice the sounds have not been generated in the vocal chords and oral cavity of a flesh and blood person, and this remains the case regardless of the fact that the sound may resemble that of a human voice very much, and may even be mistaken for one if the processing is very clever. It still does not have a source reference outside the realm of digital construction.

But although a voice cannot be constructed, it can be modified. An example of this can be found on Radiohead’s Kid A (2000), which contains all kinds of humanoid sounds and blurred transitions, from the obviously human to the obviously synthetic. The increasing use of voice modification technologies makes it interesting to enquire about the limits of the voice’s trace back to a body and a personality. If the producer changes the frequencies, at what point does the sound stop referring to a unique individual? How much reverberation can a voice sustain before it becomes unrecognizable as a trace of a body? Is there a minimum duration for which the voice must be present in the mix in order for the listener to be able to relate to it as tracing a personality?

There are no definite answers to these questions, but there is a definite tendency among music lovers. During the 1990s this type of voice modification entered the mainstream of pop music, and famous artists had huge hits where their voices were heavily modified. In 1998 Cher released ‘Believe’, and took the risk of offending some listeners’ sense of authenticity because of the way her voice was manipulated. Her producer correctly presumed that her 1990s fans would be able to hear her new recording as unproblematically representing the real Cher. In an age of widespread listener sophistication such a strategy is not a great risk to take for a popular artist. Danielsen and Maaso (forthcoming) have analysed Madonna’s ‘Don’t Tell Me’ as a good example of the specifically digital sound of modern music production. Another striking example is provided by the US artist Beck, who varies his vocal style so much that it is hard to ascribe to him an identity based on voice, and he is often associated with a postmodern pop style. On the CD Midnite Vultures (1999) Beck sings in at least three different ways. He has a kind of tough guy funky voice and a slick groovy voice, and also makes use of short bursts of a hoarse screaming voice. All these are obviously processed and overdubbed, and they are sometimes superimposed on each other.

The voice is regularly modified so much that it almost doesn’t refer to a human, but becomes a sound in a strictly material sense. I wall rely on Simon Frith to conclude how music lovers relate to this phenomenon. He argues that people engage songs by responding to the materiality of the body while singing: ‘Singing is a physical pleasure, and we enjoy hearing someone sing not because they are expressing something else, not because the voice represents the “person” behind it, but because the voice, as a sound in itself, has an immediate voluptuous appeal’ (1981: 164). This is the bottom fine of modern music listening.

The recording medium, 2008

As in chapter 2, I will outline the infrastructure of the medium in question. If the professional studios are taken as the starting point, the recording industry-is still based on a highly asymmetrical technical set-up. There are complex sound-proof studios and advanced computer systems that amateur musicians can only dream of using and that most ordinary music lovers do not even know exist. The asymmetry between production and listener techniques in effect makes up two highly advanced, but separate, sound environments. Just as there is high-quality music recording, there is high-quality domestic listening.

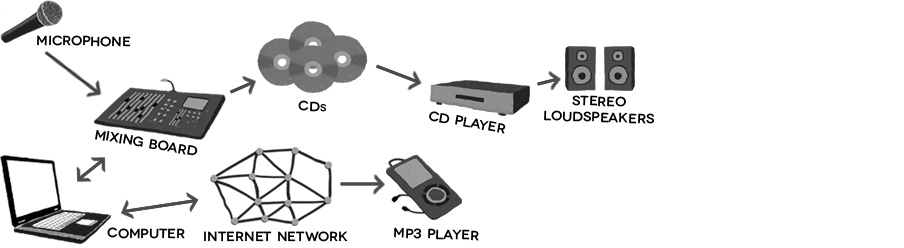

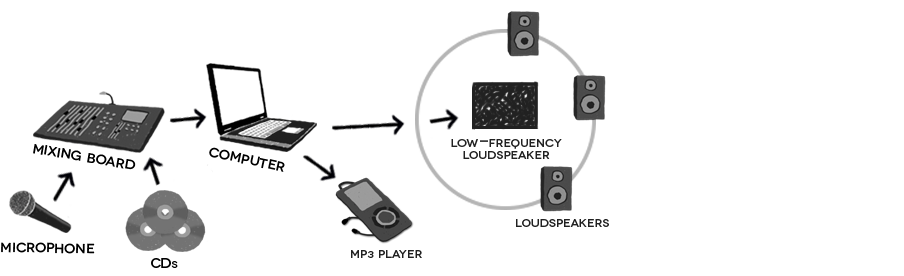

Figure 3.2 shows that there are two different distribution platforms in the current set-up of the recording medium. The CD distribution system relies on industrial copying of CDs, which are sold through music shops on the high street or through online services such as Amazon and shipped to the buyers in the post. Music lovers can listen to CDs in a range of settings, but the most advanced setting is still the high-quality stereo set with two loudspeakers centrally located in the living room. In addition to CD distribution, there is file transfer on the internet, either legally through services like iTunes or illegally on pirate services. While downloaded music can of course be listened to on the high-quality stereo set, listeners typically download music to an mp3 player and carry it with them in their daily life. This robust distribution platform seems to be taking over from the more vulnerable CD distribution system. Some music lovers still purchase LPs and play them on the old-fashioned turntable, but this platform is not included in the figure.

This chapter mainly revolves around synthetic sound, and this type of sound relies on digital carriers. I have stressed that recorded sound has become perfected to the extent that it need not refer to natural acoustic spaces at all in order to communicate. The track by Autechre demonstrates this in the simple sense that all sources are produced inside the computer, and can therefore be perfectly represented in the computer’s code.

This synthetic quality can be explained by making a historical contrast. In both tape and digital recording the ambient sound is picked up by microphones and converted to electromagnetic impulses. Digital media have one more conversion process, namely the sampling and encoding of the electromagnetic signal into binary digits. This can be done optically by a laser head (CD) or magnetically with a spinning disc (hard disc), or with solid state electronics (memory chips). Not least, a programmer can write a sound signal entirely in code, without any external influences (White 1997).

In digital recording there is no physical contact between the microphone pickup and the code on the disc, and consequently no mechanical degeneration of audio quality. In comparison, the analogue signals of tape and LPs are like satellites in low orbit, and it is only a matter of time before they are destroyed. When rearranging a sound array on magnetic tape, the tape had to be physically cut or re-recorded to another tape deck. ‘Every time it is copied or displayed, it suffers irreversible damage. Its signs are abraded and come closer to being mere and useless things’ (Borgmann 1999: 167). It was not until the advent of digital coding that sound could be considered ‘perfectly contained’ in a storage medium.

The more often an analogue signal is sampled, the more accurate its digital representation and consequent reproduction will be. The coding standard colloquially referred to as ‘CD quality’ samples each second of analogue signal 44,100 times, and in professional recording there is typically a sampling rate of 96,000 Hz (Thompson and Thompson 2000: 321ff.).The sampling process ensures that ‘there is no discernible difference between the sound recorded in the studio and the signal reproduced on the consumer’s CD system’ (Goodwin 1990: 259). In a technical sense at least there is a stable and ‘perfect’ signal equilibrium between the producing and the listening end. In the late 1980s the digital signal of CDs was marketed with the slogan ‘Perfect Sound Forever’ (Harley 1998: 255).

Sound on the screen