For and against Participation: A Hermeneutical Approach to Participation in the Media

Authors: Lars Nyre and Brian O’Neill:

Media use is a social activity, and nowhere is it more social than during participatory acts where the user is personally engaged in the public sphere and can lose face or have success in the eyes of others. This chapter deals with ordinary people’s reasons for and against participating in modern media like television, radio and the Internet. This topic is also important in a research perspective, as participation has been one of the most popular trends in audience and reception studies for the past 20 years (Carpentier 2009; Dahlberg 2001; Dahlgren 2005). The chapter presents the hermeneutic paradigm in social studies and demonstrates its relevance for participation in the media.

The chapter goes on to present a study of opinions among media participants in Norway and Ireland in 2005-2006, and as such it is intended to show an empirical application of the hermeneutical paradigm. We particularly focus on motivations for and against participation, as formulated by our informants during qualitative interviews. Informants claim that private enjoyment is the main reason for taking part in the media, whereas unsuitable formats for political debate are the main reason for not taking part. People are entertained by their own participation in quiz shows or talk shows because these formats are relatively harmless, and you do not lose face by participating. At the same time, they do not trust the political debate formats to secure their integrity and equality with others during participation. You do not lose face by giving the wrong answer to a quiz, but you lose face if you are cut off by a moderator in mid-sentence. In political formats, the participants’ integrity is constantly at stake, not because of their opinions but because of the strategies of the station. This tension between positive and negative motivation comes across as well-informed and serves as a paradigmatic example of how empirical hermeneutics works.

Hermeneutics and Participation

Before we describe our approach to participation, the hermeneutical tradition must be introduced. Hermeneutics traditionally refers to systematic text readings, for example, exegeses of the Bible, consultations of law texts or interpretations of dramatic literature. We are concerned with philosophical hermeneutics, a theory of understanding that emerged with Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911). He established an important epistemological difference between ‘explanation’ in the natural sciences and ‘understanding’ in the social sciences and humanist fields. Explanation is factual and finite, whereas understanding is intelligent and infinite. In the social sciences and humanities, language became the primary research object during the twentieth century, and along with it the act of understanding became a central topic in philosophy. The main hermeneutical writers are Hans-Georg Gadamer (1989), Jürgen Habermas (1987), Paul Ricoeur (1991) and Wolfgang Iser (1991).

The object of understanding in hermeneutic approaches is texts and actions in situations where you as a ‘reader’ revise your prejudices all of the time because you have learnt more, and if you relate to the same phenomenon a second time, you know something about it from before and can penetrate it further. This process is called the hermeneutical circle, and it has become a famous metaphor for the process of human understanding. After Gadamer it could have been renamed the hermeneutical spiral, as the faculty of understanding is inconstant development.

‘Double hermeneutics’ is another key notion in the hermeneutical tradition, and it indeed serves as the methodological core of our approach. Hans Skjervheim (1959) considers the relationship between researcher and research object in social sciences to be communicative. The people who are studied and their researchers are potential conversation partners. The natural scientists, however, cannot communicate with their research objects in this way. Anthony Giddens calls this communicative phenomenon ‘double hermeneutic’ in that it consists of a connection between two provinces of meaning: the meaningful social world of lay actors and the meta-languages invented by social scientists to describe the world. There is ‘a constant “slippage” from one to the other involved in the practice of the social sciences’, Giddens (1991: 374) states.

In this chapter, we will apply the hermeneutical approach to the study of participation in the media. Media participation must be considered an act by non-professionals, where the aim is to contribute content to the otherwise professional ‘text’ of a programme. By singing, speaking or delivering information by short message system (SMS), e-mail and so on, the participant contributes a prepared text to a programme genre that is recognizable to him or her. This strongly communicative and public character makes it possible to distinguish participation from reception (lying on the sofa), programme interactivity (using menus, time-shifting), bureaucratic service requests (upgrading your cable service) and peer-to-peer contact(calling your mother on the phone). For other conceptualizations of media participation, see Carpentier (2007), Jensen (2008), Kiousis (2002) and Siapera (2004).

‘Participation’ should not be confused with ‘interactivity’. The latter is restricted to describing the situation where a human interacts with a technology, as when a person uses the mouse and keyboard of the computer to write a message and post it somewhere. Such interactivity presumes an interface between a skilled user and a technological set-up where the apparatus and its programmes continuously change the data output according to changes in the input. Furthermore, if the interface is changed the content of the interaction is also changed. In the computer world, this implies that the user is frequently forced to acquire new skills because the functionality of the apparatus has been changed in the updated version. This is a conception where the patterns of interaction are ultimately technologically determined. This is not an accurate description of the hermeneutic act of participating.

To define participation as something more complex and fulfilling, we turn to the American sociological tradition called symbolic interactionism. Here, the important connection is that between human and human. Beyond the handling of instruments, contact takes the form of persons interpreting each other, a process of making judgments and taking action in the face of the constant actions and judgments of others. Herbert Blumer sketches the playing field of human interaction like this:

[People] are caught up in a vast process of interaction in which they have to fit their developing actions to one another. This process of interaction consists in making indications to others of what to do and in interpreting the indications as made by others. (As cited in Collins 1994: 320).

He equally presumes that we live in worlds of objects and are guided in our orientation and action by the meaning of these objects. These objects, including media technologies and content, are formed, sustained, weakened and transformed in our interaction with one another (Collins 1994: 320). In this model of participation, the entities that act on each other are equally sensitive, equally responsible for their actions and equally able to display initiative. The purpose in any case goes far beyond the activity of pushing buttons or navigating through pages. It is a form of technology-mediated participation that Andrew Feenberg refers to as ‘the most fundamental relation to reality (Feenberg 1999: 196).

What kind of interpretational behaviour is required? Ideally, citizens engage in a public dialogue that acknowledges every participant as a responsible fellow citizen. To participate in a dialogue, according to the philosopher Hans Skjervheim, is to recognize the subject matter of the other’s speech, to listen carefully and evaluate its claim to truthfulness or trustworthiness, and to move further along its interpretative trajectory when speaking yourself. “This means that I am participating or engaging in this problem, Skjervheim says in his 1957 essay called ‘Participant and Onlooker’ (1996: 71). The words take part in an on-going discourse of co-operation which could not exist without such base human bonds like trust, respect and acceptance, and their opposites during conflict and enmity. Your career, your self-esteem, your identity are all related to others through this reciprocal dimension of communication and its social repercussions. If you promise to participate, you have committed in a way that has consequences for your future communication – not with computers, but with humans.

If you want to participate in the media, you must have language-oriented skills so that you can handle the interfaces for text, sound and video in a communicative way. Media use involves knowledge about genres, formats and topics, and this knowledge is absolutely necessary to be able to play along with the programmes’ communicative style or be critical towards it. Participation also requires integrity, at least in the minimum sense of being able to tackle the pressures of public attention in a coherent way and avoid embarrassing yourself in front of everybody. The content-producing function of participation is interesting because it inspires a high level of self-reflexivity. The person in question necessarily sees himself or herself in the eyes of others. In comparison with watching a film or reading a book, the activity of participating involves nervousness, self-consciousness and the ambition to do good and save face.

Participatory behaviour can be graded according to the public exposure of skills, personality and character during participation. People who make broadcast content for example at a community radio station or a student newspaper have relatively high exposure. People who appear as contestants in talent and reality shows, or guests in talk shows, also have high exposure. Examples of moderate exposure are postings in blogs, commentary fields and chat rooms as well as voting for videos on a music TV channel and voting for the football player of the week by sending an SMS message. Since 2005, it has become quite common for people to maintain a personal profile in social media. This is a permanent low exposure that comes alongside the traditional forms of participation.

Case: Motivation for Participation

Our project is to construct a meta-language to describe people’s motivation to participate or their lack thereof. Motivation implies enthusiasm for doing something or the need or reason for doing something. Motivation may be rooted in a basic need to minimizing physical pain, eating, drinking and maximizing pleasure (Morris 1967), or it may be attributed to more hermeneutical reasons such as a state of being, an ideal, an ethical norm and so on. We distinguish between three types of hermeneutical objectives: private enjoyment, social attraction and political purpose. Below we will define this triad of reasons more carefully and quote from our empirical material from Bergen and Dublin.

Qualitative research projects often challenge people to formulate quite precisely thoughts and experiences that they may never have formulated before. Some researchers are sceptical about this slightly confrontational method (Gentikow 2005), but we consider it a fruitful approach. There are many topics that people do not really think carefully about until they are asked about it. When questioned by a small child, the adult may suddenly be required to explain what ‘gravity’ is, and during a heated discussion you are challenged to state your opinion about Islam. Such communicative confrontation scan lead to new ideals and opinion, and it would be too strict a restriction on qualitative studies if it could only deal with issues that the informant is comfortable with and knowledgeable about. Most of the justifications quoted below were provoked during the interview phase, with informants routinely saying things like ‘I’ve never really thought about that before, but…’.

Our study focuses on people in Norway and Ireland. They live in a cultural and historical context that influences the forms of communication, both in private and public life. Norway is a Protestant, social democratic welfare state with a long history of independence or lenient colonization from Danes or Swedes. Ireland is known as a Catholic-conservative welfare state with an equally strong culture of political awareness as in Norway but with a much more fractious past, including a long period of British colonization, a war of independence, followed by a civil war and later civil strife over partition. Norway did not have the same traumatic liberation from Sweden in 1905 as the Republic of Ireland did from the United Kingdom in 1921. The media industries in the two countries are approximately of the same size, with relatively homogenous audiences where regional differences are more pronounced (and less harmful) than national division. Both countries have a healthy number of local and regional independent media (Day 2009).

As our empirical material represents two national audience research cultures, we will give a brief review of each. In Norway, several studies are influenced by hermeneutics and/or cultural studies and look, for example, at participation in television formats (Gentikow 2010), dating programmes on television (Syvertsen and Bakøy 2001) and general media use by children and youngsters (Hagen and Wold 2009; Tønnessen 2007). There is also a study of opinions about participating in broadcast programmes based on the original research reported in this chapter (Bøe 2006). When it comes to Ireland, participation in broadcast programming and citizen engagement in public service broadcasting has been along-standing theme of communications research. Kelly and O’Connor (1997) examined a wide range of audience practices in mainstream media (radio, television, print) focusing on the complex interplay of power and cultural identity. The potential of communication technologies for facilitating democratic participation for media consumers was first studied by Trench and O’Donnell (1997), with further studies of their domestication in Ward (2003), Kerr (2000) and Komito (2007). Participatory media in Ireland, in particular the case of community radio, has been the subject of on-going research (Day 2009; Mitchell 2002), reflecting its importance in the Irish media landscape, whereas more recently media literacy policy has been examined from the point of view of enabling greater civic engagement (O’Neill and Barnes 2008). O’Sullivan (2005) has made an interesting qualitative study of talk radio, and Ross (2004) has studied the political dimension of participation in radio and television.

For this research project, we interviewed a total of 64 people, 32 in Norway and 32 in Ireland, during 2005 and 2006. We wanted to interview a cross-section of citizens in Bergen and Dublin. When selecting informants we created a systematic mixed population group, with gender balance, four age groups from 15+ and equal inclusion of people with basic and higher education.

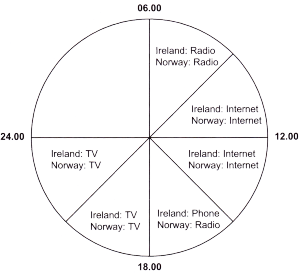

Among our informants, there was a clear tendency for Internet users to be younger and radio users to be older, which conforms to the presumption that young people will adopt new media habits quite easily, whereas older people rely on their established diet of paper newspapers and public service broadcasting. However, TV dominated in the evening among all age groups (see Figure 1).

In both Norway and Ireland 29 of 32 informants used the Internet regularly, with similar numbers regularly using SMS messaging. It may be that Ireland and Norway are in reality quite different, but both share in media and communications technology trends characteristic of western industrialized countries.

Informants completed the same questionnaire, and researchers followed the same interview guide in both countries. We used semi-structured interviews to research the diverse forms of participation in contemporary media. Based on their statements, we accumulated a list of 31 unique reasons for and against participation, and we categorized them as three types of motivation: private enjoyment, social attractions and political change.

Motivation can be studied in terms of language. Alfred Schutz distinguishes between ‘in-order-to motives’, which have a clear purpose that will presumably be reached in the future, and ‘because motives’, which are rooted in the past experiences and habits of the person (Schutz 1970:126-127). For example, you can participate to win money, or you can participate because you are sure you know the right answer. Our material requires us to introduce ‘if motives’, which have a clear purpose in the future but will only be accomplished under certain limited conditions. For example, you will participate if a friend joins you in the endeavour. These three types of motives; ‘in order to’, ‘because’ and ‘if; are used to identify reasons and categorize the empirical material.

The hermeneutic object of study can in this case be defined as a ‘reason or ‘justification formulated orally by informants and transcribed by researchers. To justify an action means208For and against Participation to explain that the motivation for it is just, right or reasonable and to show awareness of other peoples perspectives from which the justification may not seem as reasonable as it does for the participant. Justifications typically relate to things in a situated way, where the speaker starts from his or her own life experiences and branches out into generality if he or she manages. Sociologists call this held of experience ‘the common sense province of meaning’ (Schutz 1970) or ‘the lifeworld’ (Habermas 1987). Grown-ups are in general able to describe their personal experiences and perspectives in varying detail and truthfulness, and make rationalizations and justifications of their own behaviour and that of others. This type of rational speech is the raw material of our investigations.

We asked simple yes/no questions and the most important was the following: ‘Have you ever felt that you should have participated more in public debate?’ We always prompted a follow-up from the informants, and the statements made during this dialogue were the really interesting ones, as this is where justifications were formulated. Using Schutz’s distinction between motives, we identified justifications, for example, by the words ‘since’, ‘because’, ‘if’; and through a plethora of contracted formulations that explain the motivation, interest or gain from a certain action (or non-action). For example, ‘It’s stupid’ can be completed as ‘I will not participate because I consider it a stupid activity.’

Categories are always disputable. We made an interpretation scheme where we listed all the formulations of reasons our informants made, and they were more and more carefully categorized as the list grew. There are two dimensions in the organization of our findings: Dimension 1 relates to a rather theory-driven distinction between ways of formulating motivations (‘in order to’, ‘because and ‘if’), whereas Dimension 2 relates to a more inductive or grounded distinction between different topical fields of justification (‘personal enjoyment’, ‘social attraction and ‘political purpose’).

Personal Enjoyment

As stated earlier, motivation may be rooted in a basic need to minimize physical pain and maximize pleasure. It could be called egotism rather than altruism, and it is marked by the wish for monetary gain, self-promotion and personal enjoyment. The list of reasons will help to explain it better:

Yes, because it is fun.

Yes, if I don’t have to spend money on it.

Yes, in order to win prizes.

Yes, in order to compete with others and display knowledge.

Yes, if I become agitated and want to voice my opinion.

Yes, because it is easier to participate now than it was before.

No, because of stressful self-awareness.

No, in order not to be bothered.

No, because I don’t want to spend my time like this.

No, because it’s too expensive.

No, because it wouldn’t give me a valuable enough experience.

Yes, because It Is fun

A typical statement was made by Arne (15): As long as it is based on competition, it is great fun.’ Nina (37) says,

The last time I was interactive was in Easter Quiz where you can send in an SMS and join an SMS competition. The questions are damned difficult, and you are supposed to give answers until the time runs out, or you answer incorrectly. It was incredible fun, but you must have Internet because it’s so difficult.

Yes, In Order To Win Prizes

Bjarte (25) would like to call into a show on the Norwegian station Radio 1 called Hunted. ‘There was 40,000-50,000 kroner in the jackpot, so I guess that’s what made me interested.’ Kine (27) has long wanted to call a radio show where you are supposed to shout ‘stop’ at the right moment, and you can win anything from 200 to 4200 kroner. When asked why she wanted to, she answered, ‘Cash is king. No-no! But it is a good way of getting some money quickly, so that’s really the reason.’

Yes, If I Become Agitated

Participation may happen more or less spontaneously, for example, when people get annoyed with a statement they hear or read. Harald (47) wrote to the local newspaper to speak up against an unfair review of a theatre play.

Interviewee: ‘It was annoyance that made me write to the editor, you know.’

Interviewer: ‘Did you feel that it helped in any way?’

Interviewee: ‘It didn’t help in relation to the theatre play, but it helped me that I got to let off some steam.’

The result was therapeutic only, but still it contains an acknowledgement that the public is a thoroughly real space, where you can fight back on the same turf even though no one may notice.

No, Because of Stressful Self-Awareness

Carla (23) is asked whether she would like to appear on television, and she answers, ‘I would hate to be on TV actually. I would be too shy.’ Her temperament is such that she would rather write than speak. ‘It’s easier for me’, she says. This is a because-motive in Schutz’s sense; her non-participation is the result of her personal circumstances and qualities, and does not reside in any future gain like the in-order-to motive presumes. Referring to political debate shows, Carla says, ‘I think it is hard to find the confidence to participate. It is very daunting and the people who are on these shows often seem very confident and very educated and political. You know it is hard to match that.’

It is a core concern for people how they will be exposed if they go on air. The social reflexivity contained in this concern is well studied in the micro-sociology of Erving Goffman and others (see Goffman 1986; O’Sullivan 2005). Frida (23) is sensitive about her skills as a public speaker, especially about her ability to handle the complexity of public issues. She refers to a debate about gas-fuelled electricity plants. ‘Most of those who have learnt something about the topic realize that there is more than one side to it. So I would perhaps get confused if I were to talk about it [she laughs].’ Hans (28) says the same thing.

Although I have clear opinions about gas power plants, I don’t feel that I can give very good reasons for why I mean what I do. And that’s why I wouldn’t call. I think it is important to answer well and give reasons for what you mean if you are to express your opinions in public. You can’t ‘just say ‘It’s because I mean it.’

We interpret this as motivation to save face rather than a protest against formats, and as such it is a private and not political motivation (more about the latter below).

Social Attractions

The motivation for social encounters is rooted in emotional sentiments like altruism, morality or wish for consensus. People want to be together with others, or share time with others, and this activity can be almost entirely without instrumental motives while still be very fulfilling for those involved. Scannell (1996) reminds us that before anything else, radio and television are social phenomena. ‘Sociability is the most fundamental characteristic of broadcasting’s communicative ethos. The relationship between the broadcasters and audiences is a purely social one, that lacks any specific content, aim or purpose’ (Scannell 1996: 23).

Yes, in order to contribute with information.

Yes, if somebody I know is already participating.

Yes, because I like a person, group or team.

Yes, in order to allow amateurs too and not only professionals.

Yes, if media participation were a more common and respected activity.

No, in order to shield my job role from embarrassment.

No, because people who do it are stupid.

No, because so many are doing it that there’s no need for me to take part.

Yes, In Order To Contribute with Information

Clive (16) regularly contributes with information on the Web. Finn (41):

Yeah, because often people discuss things in general terms. If you are involved in something and have a lot of experience of it, and you hear somebody really misinforming or not understanding the issue, you could ring up and maybe clarify a few things.

This kind of statement could also belong to the category ‘political purpose’, but there is a decidedly social character to this motivation. It is altruistic to stop in your tracks to provide information to the public; at least this is how informants felt about it. With blogs and social media, the social satisfaction of contributing with information is greater than ever.

Yes, If Somebody I Know Is Already Participating

For example, it is important to support friends and family who appear on air in a contest where SMS voting is part of the entertainment, as your votes are likely to make a real difference for them. In principle, Viktor (23) is fed up with SMS participation. He voted for all kinds of reality shows, especially during the first seasons of Big Brother, but in the future he will only make one exception: ‘I will never vote in the future, unless close family members and relatives are in it.’ In these, the act of voting becomes more like a duty or an act of loyalty. ‘If it is family you are bound to vote a few times.’

Yes, Because I Like a Person, Group or Team

Voting programmes thrive on the allure of beautiful, talented and innocent contestants. Audience members often get hooked on a ‘favourite’ and proceed to vote incessantly to support them, all based on a quite vague impression of their talents. Trine (56) voted for a female favourite in the 2005 season of Norwegian Pop Idol. ‘I thought she deserved it because she was a good singer and a very cute and very, very nice girl’ People are charmed by such behaviour and react in highly emotional ways that are basically unforeseeable.

No, In Order To Shield My Job Role from Embarrassment

People are able to acknowledge quite pragmatically that something happens to your social role distribution if you participate in public. For example, interests in your work life can collide with media participation. Stine (27) works as an information consultant in Bergen, and she wanted to contact the local newspaper about an issue.

Interviewer: “Why didn’t you, after all?’

Interviewee: ‘I don’t know. I should have done so, but as time goes by I feel it has become more difficult because of the job I have. There is a confusion of roles in that I’m suddenly expressing opinions as a private individual when I’m a professional information worker and am supposed to be neutral. I will be connected with that job in any case, so now it is difficult!

No, Because People Who Do It Are Stupid

The refusal relates to negative personal identification. In particular, it comes about towards people who seem socially incompetent. Victor (23) is full of contempt for unintelligent participants.

If you are sitting watching for example Tabloid [current debate on TV], and listen to the comments that are sent afterwards [he sighs and laughs], you notice that there are many idiots among us. It’s strange that they exist, really. It’s the politicians who are really good at presenting their case, and callers often hurt their cause when they present things the way they do.

Victor seems to be a person of strong negative and positive attachments to people.

No, Because I Won’t Be Treated with Civility

Lise (47) thinks the SMS fortune-telling programme contains a fruitless social coercion.

I think it is unstructured, chaotic and disrespectful for both parties. As a listener I also felt offended by this form. This form makes the callers appear as idiots, and it lies in the format itself – although the people who call in are not exactly the world’s brightest.

Political Purpose

Political motivation is rooted in recognition of society’s collective need to minimize physical harm and maximize material gain, and to promote a certain political system and more or less contested values for the development of society. We focus on the degree to which our informants think that political purpose can be channelled through participation in the media.

The final list of justifications deals with political debate. Joshua Cohen argues that democracy requires the citizens not only to be free and equal but also to behave in a ‘reasonable’ way. This means that everybody must defend and criticize the issues at stake in ways that other citizens, as free and equal individuals, have reason to accept (as cited in Mouffe 2000: 90). Amateur participants in the media cannot be exempted from this requirement. They too are required to be prepared to explain their position on any given public matter, and our informants are very much aware of this requirement – although they may not therefore feel that they satisfy it. John Dewey (1960) calls the successful performance of public reasoning a type of ‘well-considered’ or ‘intelligent’ behaviour. Dewey’s anthropology generously presumes that citizens are aware of the complexity of the society in which they live, in our case the media society with a largely digitalized public sphere. The more awareness there is about editorial and communicative strategies among citizens who participate in public, the better the public sphere will become.

In a political sense, the purpose of public speaking is to create concrete change in some province of reality, for example, by persuading somebody to change their opinion or to cause action to be taken by one or more people in a specific case. C. Wright Mills requires that ‘opinion formed by [public] discussion readily finds an outlet in effective action, even against – if necessary – the prevailing system of authority’ (quoted in Habermas1990: 358). Informants have a quite realistic assessment of their opportunities in this regard. In real life, laypersons do not have much influence on the media, and they know it well.

Yes, if I have a well-informed opinion.

Yes, in order to become more well-informed and resourceful.

Yes, because I’m engaged in my local surroundings.

Yes, because it is every citizen’s right to participate.

Yes, because it is every citizen’s duty.

Yes, because it would have worked well.

No, because it is every citizen’s right not to participate.

No, in order to keep the public sphere as professional as possible.

No, because I’m not sufficiently competent.

No, because it wouldn’t change things anyway.

No, because I don’t trust the formats/genres.

Yes, Because It Is Every Citizen’s Right to Participate

Kai (25) considers public speaking a desirable and valuable political right. ‘After all, we’re talking about the people who walk the streets and live in this country, and when an issue is relevant for more than one person the others must also have their say’ Kristin (51) considers it a human right to express oneself in public. “Well, yes, it’s a human right. Those who are preoccupied with something must be allowed to express themselves about it. I express myself about everything I’m concerned with!’ George (63) was a young man of 16 years when the Troubles in Northern Ireland started in 1969.

At the time of the Troubles, I had a lot to say and I said it to my friends, but we should have said it out loud. There was a lot of anger and a lot of stupidity, and then a lot of violence and condemnation and everything else. There wasn’t much reflection on ‘putting this into context’ or ‘could we say this in a calmer way’. So I am sorry I didn’t write to the papers or ring in to the radio.

No, Because It Is Every Citizen’s Right Not to Participate

Interestingly, this is just another version of the justification discussed above. A widespread sentiment among the informants is that they have the political freedom not to act publicly. Fred (15) is a believer in extensive liberal rights. ‘Do you think the audience should be more active in the public?’ ‘No’, Fred says.

They must be allowed to do as they please about that. I don’t think they ought to do anything at all. I have no wish that people should participate if they don’t want to participate or participate more than they do now. It’s all up to themselves.

Yes, Because It Is Every Citizen’s Duty

Alongside the consciousness about the right to speak in public (and the right not to do so), there are sentiments about a collective obligation or duty to participate, and these could be labelled ‘social democratic’. Several informants focus quite adamantly on the individual’s responsibility to improve the public. Dan (64) says,

I am of the opinion that you can’t just criticize without letting others speak up. It’s like you can’t criticize the politicians and then not vote afterwards, that’s just bullshit. If you are part of the community and you are a voter, then you can also criticize things. It’s the same with the media. You can’t criticize them without bringing in another suggestion yourself.

Dan’s justification for public participation is explicitly normative and requires active and resourceful behaviour on the part of the citizens. A democracy needs participation from all its citizens to work properly, and therefore it is a duty to participate.

No, Because I Don’t Trust the Formats/Genres

Informants are critical of what they conceive of as the lack of common courtesy in the way hosts treat callers to radio and television. Indeed, these criticisms were often eloquent and rich in detail. Stine (27) feels uncomfortable with the typical social setting of participation programmes:

There are so many debates where a private person, or the man on the street, is supposed to talk about this and that. But they are not allowed to speak for very long, or they are interrupted all the time. There is a pattern here that makes me turn it off; I get more and more annoyed and cannot listen any more. On Tabloid and programmes like that, the debate moves so quickly; there are so many opinions, but nobody is discussing things. They just throw out arguments, and it’s not the good arguments that come across; what counts is to scream loudest.

Kari (20) comments more specifically on the screaming and shouting:

In those discussion programmes, almost nobody gets their opinion across; everybody just [baaaauu] screams in each other’s face, and then there’s a politician who speaks a little once in a while. Often when an ordinary person opens his mouth it takes 2 seconds before they are told that what they’re saying is wrong.

Conclusion

We believe hermeneutics is a well-suited paradigm for studies of the conscious level of media activities, where justifications and explanations are prompted by researchers and the double hermeneutics is at work. People who reflect on their own behaviour make statements that are interpreted by social researchers.

Our case study of motivation was meant to demonstrate the fruitfulness of the hermeneutical approach, with people in Bergen and Dublin making up our interview panel. To sum up the analysis, there is an interesting tension between wanting to participate in entertaining and competitive contexts, and not wanting to participate in political debate.

Polat (2005) asks why people do not participate in the context of political Internet use:

It may be the case that people do not participate simply because of matters of convenience such as lack of time or proximity. However, if the lack of political participation stems from a lack of resources of motivation, the potential of the Internet will become less significant. (Polat 2005: 454-455)

This position suggests that there may be insufficient energy or political willpower among people, and that this can hamper the development of participatory practices on the Internet.

Our suggestion is that people want a proper discourse ethics in the media. Ordinary people are media savvy, and they know a lot about genres, formats, programmes and presenters. Their criticism can be read as a wish for discourse ethics in the sense that Stanley Deetz defines it. He says, ‘Every communicative act should have as its ethical condition the attempt to keep the conversation – the open development of experience – going’ (Deetz 1999:151). Informants do not consider the media debates to be open but closed and prejudiced. As seen in the analysis above, informants frown upon ad hominem argumentation, where the person is targeted instead of the arguments, and they are frustrated by the inability of hosts and participants to really listen to each other. Their discourse ethics means that everybody must discern and respect the rights of others. They must listen as well as speak and be able to follow up the ideas and problems of others instead of taking turns presenting monologues to each other (Skjervheim 1996). It is interesting, but not surprising, that the age-old desire for dialogue is so prominent in our material.

References:

Boe, T., 2006. Hva synes publikum om å delta i medier? En kvalitativ analyse. Bergen, Norway: University of Bergen.

Carpentier, N., 2007. Participation and interactivity: Changing perspectives. The construction of an integrated model on access, interaction and participation. In V. Nightingale and T. Dwyer, eds, New media worlds. Challenges for convergence. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 214-230.

Carpentier, N., 2009. Participation is not enough. The conditions of possibility of mediated participatory practices. European Journal of Communication, 24(4), pp. 407-420.

Collins, R., 1994. Four sociological traditions. Selected readings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dahlberg, L., 2001. Democracy via cyberspace. Mapping the rhetorics and practices of three prominent camps. New Media & Society, 3(2), pp. 157-177.

Dahlgren, P., 2005. The Internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation. Political Communication, 22, pp. 147-162.

Day, R., 2009. Community radio in Ireland: Participation and multiflows of communication. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Deetz, S., 1999. Theoretical approaches to participatory communication. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Dewey, J., 1960. Theory of the moral life. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. (Originally published 1908.)

Feenberg, A., 1999. Questioning technology. New York: Routledge.

Gadamer H G, 1989. Truth and method. New York: Crossroad. (Originally published 1960.)

Gentikow B, 2005. Hvordan utforsker man medieerfaringer? Kristiansand, Norway: IJ-forlaget.

Gentikow B, 2010. Nye fjernsynserfaringer. Teknologi, bruksteknikker, hverdagsliv. Kristiansand, Norway: Høyskoleforlaget.

Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge,UK: Polity Press.

Goffman, E., 1986. Frame analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. Boston, MA. Northeastern University Press. (Originally published 1974.)

Habermas J. 1987. The theory of communicative action. London: Heinemann.

Habermas, J. l990 Strukturwandel der Offentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der burgerlichen Gesellschaft. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Hagen, I. and Wold, T., 2009. Mediegenerasjonen. Barn og unge i det nye medielandskapet. Oslo, Norway: Samlaget.

Iser, W. 1991. The act of reading. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. (Originally published in 1978).

Jensen, J.F. 2008. The concept of interactivity revisited: Four new typologies for a new media landscape. In M. Darnell et al. eds, UXTV ’08 proceedings of the 1st international conference on designing interactive user experiences for TV and video. New York: ACM pp 129-132

Kelly, M. and O’Connor, B„ 1997. Media audiences in Ireland: Power and cultural identity. Dublin, Ireland: UCD Academic Press.

Kerr, A., 2000. Media diversity and cultural identity: The development of multimedia content in Ireland. New Media and Society, 2(3), pp. 286-312.

Kiousis, S, 2002. Interactivity: A concept explication. New Media & Society, 4(3), pp. 355-383.

Komito, L, 2007. E-governance in Ireland: New technologies, local government and civic participation. Dublin, Ireland: Geary Institute at the University College Dublin.

Mitchell C , 2002. On air/off air: Defining women’s radio space in European women’s community radio: In N. Jankowski and O. Prehn, eds, Community media in the information age: Perspectives and prospects. New York: Hampton Press, pp. 85-105.

Morris, D., 1967. The naked ape. A zoologist’s study of the human animal. London: Cape.

Mouffe, C, 2000. The democratic paradox. London: Verso.

O’Neill B and Barnes, C, 2008. Media literacy and the public sphere: A contextual study for public media literacy promotion in Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: Broadcasting Commission of Ireland.

O’Sullivan, S., 2005. ‘The whole nation is listening to you’: The presentation of the self on a tabloid talk radio show. Media, Culture and Society, 27(5), pp. 719-738

Polat, R.K., 2005. The Internet and political participation. Exploring the explanatory links. European Journal of Communication, 20(4), pp. 435-459.

Ricoeur P. 1991. From text to action. Evanston, II: Northwestern University Press.

Ross, K.’, 2004. Political talk radio and democratic participation: Caller perspectives on Election Call Media, Culture and Society, 26(6), pp. 785-801.

Scannell, P., 1996. Radio, television and modern life. Oxford, UK: Blackwell

Schutz, A., 1970. On phenomenology and social relations. Selected writings. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Siapera, E., 2004. From couch potatoes to cybernauts? The expanding notion of the audience on TV channels websites. New Media & Society, 6(2), pp. 155-172.

Skjervheim, H., 1959. Objectivism and the study of man. Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo.

Skjervheim, H., 1996. Deltakar og tilskodar og andre essays. Oslo, Norway: Aschehoug.

Syvertsen, T. and Bakoy, E., eds, 2001. Sjekking på TV: Offentlig ydmykelse eller bare lek? Oslo, Norway: Unipub.

Tonnessen, E.S., 2007. Generasjon.com. Mediekultur blant barn og unge. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

Trench, B. and O’Donnell, S., 1997. The Internet and democratic participation. Uses of ICTs by voluntary and community organizations in Ireland. Economic and Social Review, 28, pp. 213-234.

Ward, K., 2003. An ethnographic study of Internet consumption in Ireland: Between domesticity and the public participation. Key deliverable to the European media and technology in everyday life network. Dublin, Ireland: ComTech Centre, Dublin City University.